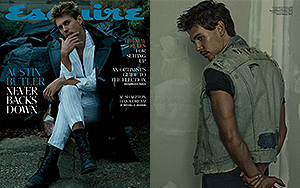

The Actor Who Would Be King: Austin Butler’s Journey to Elvis

Jen Wang

April 21, 2022

I’d like to be able to see your face,” Austin Butler says to me when we meet for the first time outside of Los Angeles’s Griffith Observatory, panoramic views of the Hollywood sign, the San Gabriel Mountains, and downtown L.A. all around us. While it may sound like a pickup line, particularly when delivered by the boyishly handsome Butler—in a husky drawl traceable to the actor’s titular role in Baz Luhrmann’s forthcoming biopic, Elvis—he’s talking about our masks, barriers that make the self-described shy “wallflower” all the more diffident. The county has just dropped its outdoor mask mandate, but they’re still required in the immediate vicinity of the Observatory, where locals, tourists, and a busload of Air Force Junior ROTC cadets—odd ducks in their pressed blue uniforms—have all converged on this 72-degree February day.

So we find a sunny spot to unmask on the terrace at the End of the Universe, the stargazing landmark’s on-site café. Butler explains that this is one of his favorite places in the city, in no small part because of its connection to James Dean and Rebel Without a Cause, the 1955 Nicholas Ray drama that anointed Dean an icon of youth rebellion. “James Dean was the actor I obsessed over as a kid,” Butler says. “I watched Rebel Without a Cause so many times.” East of Eden too, he tells me, describing how the television at his father’s house was always tuned to Turner Classic Movies. “It seems almost impossible what Dean was doing,” Butler says, “the animalistic power that he had.” Elvis Presley reportedly revered Dean, aspiring to emulate his movie career before being steered toward less serious fare by his longtime manager, Colonel Tom Parker, played by Tom Hanks in Luhrmann’s film. (Their relationship is at the heart of the new movie.)

Butler was born and raised in Anaheim, California, and the location of his childhood home was the stuff of kid fantasy: situated midway between Disneyland and Knott’s Berry Farm. His father, David, a commercial real estate appraiser, and late mother, Lori, who ran a day care at home, divorced amicably when Butler was seven, and Austin and his older sister, Ashley, moved fluidly between their respective houses. Though his family, by Butler’s own admission, “didn’t have much money,” his mother would splurge on Disneyland season passes for her children and occasionally take them there for a day of hooky just because.

Growing up in the shadow of the Happiest Place on Earth turned out to be a harbinger of Butler’s early career. After tagging along with a relative to a commercial audition at age 12 and booking the spot, the bright-eyed performer worked steadily for the next decade on Disney, Nickelodeon, and CW shows, where his good looks and sweet disposition often relegated him to one-dimensional boyfriend roles. “I was sort of embarrassed about some of the things that I had to do—but I had to cut my teeth somewhere,” Butler says. “So I decided to treat each one of these jobs as a way to grow.” Eventually, though, a feeling of stagnation set in, and Butler contemplated quitting acting altogether. Having worked half his life in front of the camera, he thought he might try to step onto the other side of it, buying the “nicest camera” he could afford.

But then a week later, he received an unexpected call from his agent about the Broadway revival of Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh with Denzel Washington. Butler, who has a workman’s approach to his craft, spent days with his acting coach, Larry Moss, painstakingly creating his audition tape—the first “short film” he shot with his new camera—and handily won the part of the deeply troubled 18-year-old Don Parritt.

Around the same time, Butler also began quietly rebuilding his résumé with supporting roles in films by some of America’s most celebrated auteurs, like Jim Jarmusch and Quentin Tarantino. In Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood, Butler, looking simultaneously underfed and glutted with malice, is almost unrecognizable as real-life Manson Family murderer Tex Watson. There’s a scene in the third act opposite Brad Pitt, who plays aging stuntman Cliff Booth on an acid trip so far out he can’t tell whether Watson is real or not, in which Butler delivers one of the most memorable lines in the film: “I’m as real as a donut, motherfucker.”

Real is a word appropriate for Butler, who exudes the unaffected vulnerability that Dean was celebrated for. He’d appeared in only one other stage play before The Iceman Cometh and expected, as he puts it, to “get torn apart in New York.” But The New Yorker’s critic Hilton Als singled out his performance in the 2018 revival, and his alone, for praise. “He wants to do right by O’Neill,” Als wrote of Butler, “his director, and his fellow-players. And, no matter how much they bray around him, he stands his ground, reacting to what may be pure in them, as performers, with his own purity, the wellspring of his work, which is that of a potentially great artist.”

When I bring up this review, Butler blushes and shrinks a bit with discomfort, but clearly the moment was pivotal. With a successful Broadway debut under his belt, Butler returned to Los Angeles. At Christmas, he remembers, “I was actually driving up through Griffith Park”—gesturing to our surroundings with his large hands, a physical similarity he shares with Presley—“and Elvis’s ‘Blue Christmas’ came on. I was singing along with it when my friend had kind of an epiphany: ‘You need to play Elvis.’ ” That friend was High School Musical alum Vanessa Hudgens, Butler’s ex-girlfriend of nine years. Butler, who had taught himself piano and guitar at a young age, practicing the six string so much he used superglue to mend his bleeding fingers, started thinking about securing the rights to Presley’s life story. Then, the opportunity landed on his front step: Luhrmann was working on an Elvis script. “It felt like the stars were aligning,” Butler says. “I just said, I’m going to dedicate everything I have to this.”

He began by listening to Elvis Presley’s entire catalog, in chronological order, while painting the Los Feliz house he had just moved into. Butler then felt ready to record an audition for Luhrmann. “I taped ‘Love Me Tender’ in my bedroom,” he says. “But when I watched it back, it was an impersonation. It wasn’t truthful, you know?” Dispirited, he went to bed, only to be woken hours later by a bad dream. “I had this nightmare that my mother was alive again, but dying. And it felt so fresh and painful.” In 2014, Butler lost his mother and “best friend”—who shuttered her own business to support his career—to cancer. Presley suffered the same loss. “I’d been watching all these documentaries and learned a couple days prior that Elvis’s mom had passed away when he was 23, the same as me,” Butler says. “I thought he probably had nights where he woke up from nightmares like this. So what can I do with that?”

He reached for his camera again. “I sat down at the piano in my bathrobe and just started fiddling,” he says. “I’d been practicing ‘Unchained Melody’ for a while, but I’d always been singing it to a lover. That night, I sang it to my mom. I wasn’t trying to look and sound like Elvis. I wasn’t trying to do anything but take that emotion and pour it into the song.”

Presley’s attachment to his mother, Gladys, was no small detail according to Southern historian William Ferris, producer of the Grammy-winning box set Voices of Mississippi. Ferris theorizes that the relationship between mother and son is a key to the singer’s enduring legacy: “One thing that still resonates about Elvis, this poor country boy, is the sense of innocence, of naivete, with which he launched a career,” says Ferris. “He just wanted to make a record for his mother.”

That record was the ballad “My Happiness,” which Elvis paid four dollars to lay down at Sam Phillips’s legendary Sun Records in Memphis as a birthday present for his mother, or so the legend goes. Presley would go on to record some two dozen more songs at the Sun Records studio—where Howlin’ Wolf, Johnny Cash, and B.B. King all launched their careers—before switching management to the Colonel.

Butler’s audition tape floored Luhrmann, who had reportedly been considering other, better-known contenders for the lead, like Miles Teller and Harry Styles. “What I heard vocally, and more importantly, what I saw emotionally, was something that simply couldn’t be ignored,” Luhrmann tells me from Australia, where he’s still editing his film. “From the moment I met Austin, he was carrying something of Elvis with him. He had a hint of the swagger, a touch of the sound.”

Despite all of the hard work, and kismet, that led to Butler to this point, the film almost didn’t happen. In March 2020, days from the start of Luhrmann’s shoot in Australia, COVID-19 hit. (You may recall that Hanks and his wife Rita Wilson fell ill there, becoming Celebrity Patients Zero and One.) Production was suspended indefinitely, and cast members started to return to the States to be closer to family and loved ones. But Butler stayed. “If I fly back [to the States],” he recalls, “I’m going to lose my momentum. I’m going to be balancing real life and prep. Unless I immerse as much as I possibly can, I’m going to feel like a fraud.”

Living alone and socially distanced in an oceanside apartment on the Gold Coast of Australia, Butler created an unusual nest for himself. “I made the entire place look like a detective film, where there’s images of everything connected with the strings and stuff,” he says, describing the evidence board, or so-called crazy wall, he created of Presley’s life. “I did have days of feeling lonely,” he admits, “and, at one point, I went three months without a hug. That was really rough.”

Production resumed in September 2020, and what should have been a five-month shoot turned into 11, which Butler likens to being plunged into an alternate reality. “I had so many hours of being put into the deep end of fear,” he says. One of those challenges, given his natural reserve, was getting up in front of 600 extras in a bedazzled jumpsuit and electrifying the crowd the way Presley did so effortlessly—or so it seemed. “I learned that Elvis was very shy as a kid, and he would ask people to turn around when he played the guitar and turn off the lights in the room,” he says. “And I thought, that’s how I feel now. But he overcame that. So how can I?”

The answer turned out to be a simple exercise in thermodynamics. “When energy is on me, I get shy. But as soon as I poured it out, and I was trying to make this girl laugh and that girl blush, then fear went out the window,” he explains. “It was an energetic exchange that was really beautiful. I finally understood the addiction that performers have to being onstage.”

Elvis’s production and costume designer Catherine Martin, Luhrmann’s wife and career-long collaborator, echoes Butler’s account. “The audiences in the movie aren’t screaming because someone yelled at them to. They went crazy because of the energy of his performance.” Martin ascribes Presley’s appeal to the combination of “a flamboyant kind of feminine dressing with this incredibly raw, masculine sexuality,” groundbreaking at the time. The film has Butler in nearly 100 costumes, and three looks in particular that made the cut exemplify that gender fluidity. A 1950s pink suit re-created from the archives of Lansky Bros., the Beale Street clothier to R&B royalty; a black leather jacket and matching pants first designed by costumer Bill Belew for Presley’s ’68 Comeback Special; and, for The King’s Vegas years, a cream-colored caped B&K jumpsuit, another Belew re-creation embroidered for the film by the original garment’s sewing artisan, Gene Doucette.

“Poor Austin,” Martin—a mother of two with Luhrmann—says protectively of their star. “He spent hundreds and hundreds of hours patiently standing for fittings, and this after hours of rehearsals. In one sitting, I think we did 25 jumpsuits and three different body types. You had to check yourself because he’s so willing to go the extra mile that you could take advantage of that. You actually had to ask, ‘Hey, have you had a glass of water?’ ”

No stranger to immersive acting experiences, Hanks gave Butler some friendly advice when he saw his onscreen protégé getting too lost in the role: Commit to one thing a day that has nothing to do with the job. “Making a film, especially this one, is an all-in, relentless marathon. The body and psyche take on a heavy burden,” Hanks explains. “An actor’s soul benefits from some daily detour. A film you’ve never seen before. A trek to that mountain in the distance.”

Elvis isn’t due till June, but paparazzi have already been following Butler and his new girlfriend, model Kaia Gerber, the last few months across continents—London to L.A. (Gerber, coincidentally, dressed up as Priscilla Presley for Halloween in 2020.) The only allusion Butler makes to his significant other, daughter of Cindy Crawford and Rande Gerber, is when he talks of his love for the ocean. He divulges that until recently, he’d never spent much time in Malibu—Gerber’s hometown—where he’s been hanging out quite a bit at his “friend’s parents’ house.”

Butler tells me it still surprises him that people know who he is—even as a woman and her daughter approach to ask if she can take a photo. Butler graciously obliges while I snap two pictures that, judging by the phone’s settings, are likely ending up on Instagram, a platform on which Butler spends little to no time. He’s taken Hanks’s old-school advice to heart, and his “daily detours” from work involve reading nonfiction that skews toward the spiritual—Ram Dass and Jon Kabat-Zinn are mentioned in conversation—toggling between meditation apps like Waking Up and Headspace at the beach, and road-tripping to reconnect with his family, who have all moved away from Southern California. Oh, and he still has that camera.

“I haven’t had time,” Butler admits, of trying his hand at directing. After wrapping Elvis, he headed straight to London to film a lead role in Masters of the Air, a Band of Brothers-in-the-sky limited series, executive-produced by Hanks and Steven Spielberg. “I look forward to the day when I can dedicate myself to that,” he says. Judging by how swiftly his star is rising, that day may be on a distant horizon.